When it comes to improving reliability in your plant, culture is key to your long term success. Without establishing the right culture your hard-won improvements will simply erode over time. And before you know it, you’ll be back in that vicious cycle of reactive maintenance. But what is reliability culture? And how do you measure it? Can you even measure it? In this article, I will introduce the “Reliability Culture Ladder”. It is a simple concept to help you assess your reliability culture.

A Word of Warning:

This is a long, in-depth article. I share in detail how I explored the concept of reliability culture. And I discuss various models and industry sources that I used to develop the Reliability Culture Ladder. In the coming weeks, I will summarise this article in something a bit shorter, more digestible.

What Is Organisational Culture Anyway?

But before we delve deeper into reliability culture and how to assess it, we need to get clear on what organisational culture is.

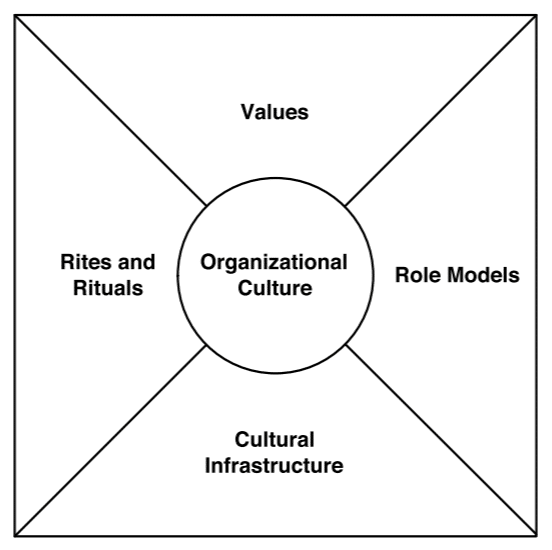

In the book “Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life” the authors Terrence E. Deal and Allan A. Kennedy explore how corporate culture impacts the success of an organization. And in their book, Deal and Kennedy identify four key elements of corporate culture.

The first element is Values. Values are the core beliefs and principles that guide an organization’s decisions, actions, and behaviours. They form the foundation of the corporate culture. And provide a framework for how employees should act and treat one another.

Values may include:

- integrity

- teamwork

- innovation

- customer focus

- or other shared ideals that the organization deems important.

A strong corporate culture is one where these values are clearly communicated, understood, and practiced throughout the organization.

The second element of organisational culture that Deal and Kennedy defined in their model is what they called “Heroes”. Heroes are individuals who embody and exemplify the organization’s values and culture. These individuals may be current employees. Past employees. Or even founders of the organization.

Heroes serve as role models for other employees. They demonstrate the desired behaviours and attitudes that support the company’s values. By sharing stories of these heroes and their accomplishments, organizations can inspire and motivate employees to embrace the corporate culture and strive for similar achievements.

The 3rd element of organisational culture as defined by Deal and Kennedy are so-called Rites and Rituals. Rites and rituals are formal and informal practices, ceremonies, and traditions that help reinforce the organisation’s values and culture. They can include things like:

- regular staff meetings

- company-wide events

- celebrations of success

- informal gatherings, like team lunches or after-work social activities

Rites and rituals serve as a way to bring employees together. They foster a sense of belonging and unity. And help to reinforce the shared values and cultural norms within the organization.

The fourth and final element of organisational culture is the cultural network. The cultural network refers to the informal communication channels and relationships that exist within an organization. These networks play a crucial role in transmitting and reinforcing the organization’s culture. Gossip, storytelling, mentoring, and other informal interactions are all part of the cultural network that helps to disseminate information, share knowledge, and maintain the organization’s culture. By understanding and leveraging these networks, companies can ensure that their values and culture are effectively communicated and embraced by employees throughout the organization.

Together, these four elements help to create, maintain, and strengthen a company’s corporate culture. And ultimately influence the overall success and effectiveness of the organization.

I discovered this model for organisational culture when I read the book “Improving Maintenance and Reliability through Cultural Change” by Stephen J Thomas. In the book, Thomas built on this model from Deal and Kennedy to create a diagram reflecting the four elements of culture but with ‘Role Models’ replacing ‘Heroes’:

Figure 1: Diagram …

One area where I disagree with both the model proposed by Deal and Kennedy and the diagram created by Thomas is that neither include, or seem to place much importance on work processes. That may not be essential when looking at corporate culture at a high level, but when using this approach for reliability culture I believe the inclusion of work processes is key.

Work processes formalise how work is done, and as such strongly influence reliability culture. Poorly defined, loose, inconsistent, or simply missing work processes will drive you to a much more reactive reliability culture. Whereas well-defined, well-executed processes can reinforce a proactive culture even to new members of the organisation.

The other aspect that bothers me with these models is that they use terminology that is not commonly used or understood in our world of maintenance and reliability. The benefit is that since these terms are relatively unknown you can clearly define them, but I feel that these unfamiliar terms will simply put off many potential users and readers who live in the ‘real world’.

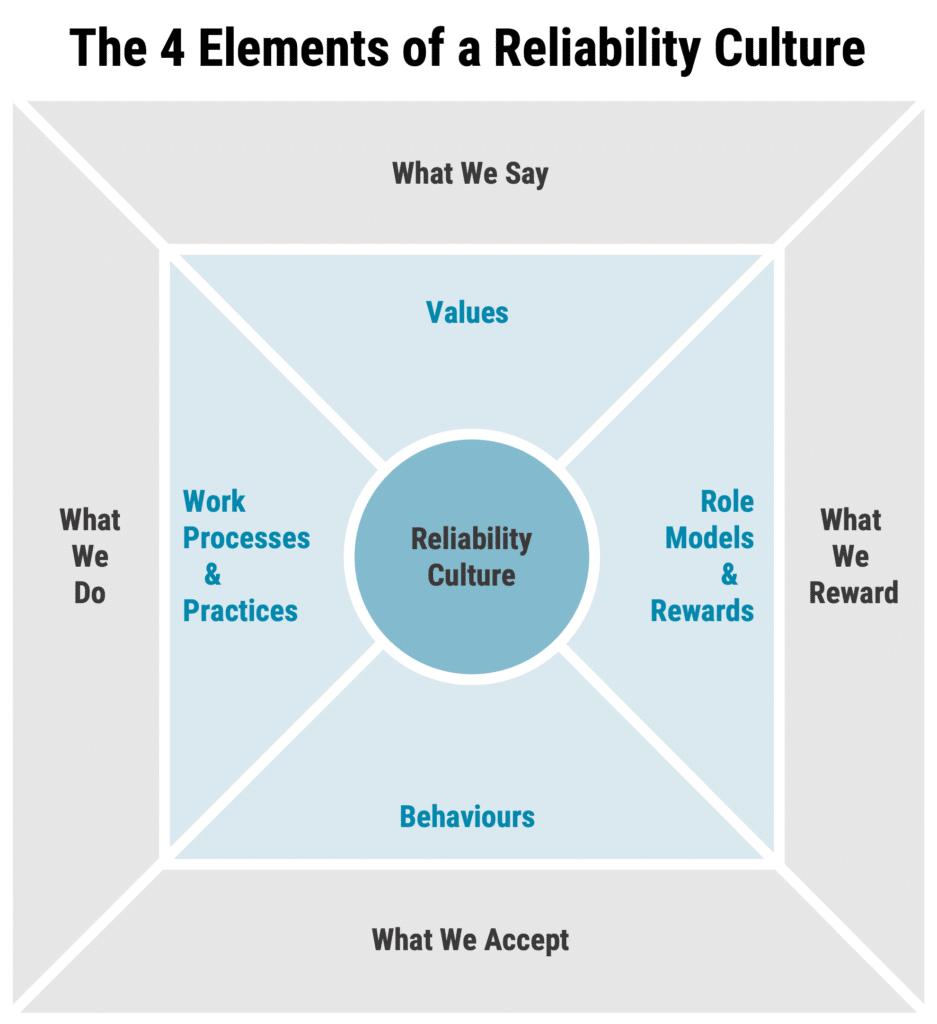

Anybody who has read my articles knows that I am a big fan of making things simple. As simple as they can be, just not simpler (to paraphrase Albert Einstein). So, in the diagram below I have further developed the diagram from Thomas’s book to create what I feel is a more practical, more day-to-day view that we can more easily use to communicate with our teams:

Figure 2: The 4 Elements of Reliability Culture, derived from the diagram in Improving Maintenance & Reliability Through Culture Change by Stephen J. Thomas, 2005, Industrial Press.

In my adaptation, the first element of ‘Values’ remains unchanged. Values are our core beliefs and principles. These are typically reflected by what we say, like “reliability is important” or “safety is a priority”.

In real life, what we say is often contrasted by what we do. And that is reflected by our work processes and practices; with practices including some of the informal ways of getting things done in an organisation.

And for the concept of Heroes or Role Models as Thomas referred to, I have added “rewards”. When it comes to culture what you say is important, what you do is even more important but what you reward is key to your success. Sure, people respond to role models. But, I strongly believe people respond even stronger to how they are rewarded and recognised. Keep in mind that “rewards” is not just financial rewards. Also, keep in mind that when it comes to ‘role models’ one of the most powerful aspects there is to ensure that our managers and leaders personally exhibit the right behaviours and work practices that align with what is said.

In addition to what we say, what we do, and what we reward there is one last, final essential aspect that we need to address and that is ‘what we accept’.

‘What we accept’ reflects in essence the behaviours we accept from our people. This is a slightly simplistic but, in my view, practical way to frame the concept of the Cultural Network as defined by Deal and Kennedy.

With that, we have an effective but easy-to-understand description of the elements that make up a reliability culture:

- Values

- Work Processes & Practices

- Role Models & Rewards

- Behaviours

But how do we go about assessing a reliability culture? And how can we reasonably objectively compare the reliability culture of one organisation to that of another?

Why You Should Measure Reliability Culture

Culture is a complex and dynamic concept that can vary greatly between organisations. Even within an organisation, culture can vary a lot, as different sub-cultures may co-exist in different parts of the organisation. And culture is not something static, but rather something that evolves and adapts over time.

That (natural) evolution is one reason why it is good to be able to assess a culture. The main reason is of course that establishing a reliability culture is critical to your longer-term success. As described in my Road to Reliability Framework™ you need leadership to implement change. But you need culture to sustain those changes. So you need to understand to what extent you have established the right elements of your reliability culture to be able to understand if you are likely to be in a position to sustain the hard-fought improvements.

The complexity and variability of culture make it difficult to “measure” culture in the traditional sense. Just like you can’t go to the shop and purchase yourselves a few pounds of reliability culture, you can’t pull out a measuring tape and see how much culture you have.

The only option we have is to conduct some form of indirect measurement, an assessment of the elements that make up a reliability culture. And it’s important to note that these assessments – these snapshots of culture at a point in time – are not always entirely accurate and may not capture every aspect of culture. However, they can still be useful in identifying areas of strength and areas for improvement within an organization’s culture.

How to Assess Culture

When you investigate industry resources, you’ll quickly find that a range of ways is proposed to measure or assess company culture, including:

- Surveys: Surveys can be used to gather feedback from employees about their perceptions of the company culture. These can include questions about things like the values and behaviours that are most important to them, as well as their overall satisfaction with the culture.

- Focus groups: Focus groups can be used to gather more in-depth insights into the company culture by bringing together a small group of employees to discuss their experiences and perspectives on the culture.

- Observations: Observing how employees interact with each other and with customers can provide valuable insights into the company culture.

- Interviews: Interviews with employees, managers, and leaders can provide insight into the values, behaviours, and norms that shape the company culture.

- Metrics: Some organizations track metrics related to the company culture, such as employee turnover, engagement, and satisfaction. These metrics can provide a quantitative measure of the culture.

Ideally, you use a combination of these approaches to get a well-rounded understanding of the company culture, but we need our approach practical because if we allow culture assessments to become massive undertakings than it is no longer a tool we can easily use. As we discussed, culture is not something that is directly controlled. Instead, it emerges from a complex interaction between the 4 elements of culture we defined earlier. That means however we set out to assess a reliability culture it will inherently not be as objective as we might like it to be. Therefore, it is essential to involve employees in the assessment process, as they are the ones who experience the culture on a daily basis.

Although the assessment or our reliability culture may not be fully objective, and may by definition be somewhat flawed having that snapshot-in-time of your reliability culture can be immensely valuable as it provides a clear statement that the organisation can engage with.

Now that we have an understanding of what elements make up a reliability culture and how we might go about assessing an organisation’s reliability culture, it’s time to find or develop a model for reliability culture that we can use to describe any assessments we might conduct. Without a model, our assessments would likely become too subjective and not really comparable over time or between organisations.

Existing Models for Reliability Culture

Terms such as a ‘proactive culture’ or ‘reactive culture’ are often used in our industry, but as far as I know, there are no models defined that clearly demarcate a proactive reliability culture from a reactive one.

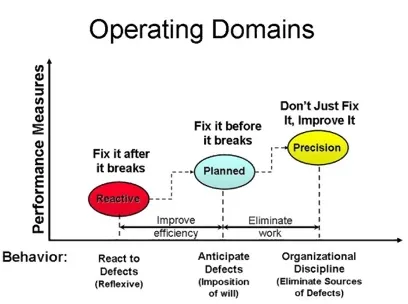

Within the maintenance & reliability community probably the most well-known depiction of reliability maturity is Ledet’s Domains of Operation and although it is not a model for reliability culture it is worth exploring in a bit more detail before we develop a model to assess reliability culture.

In 1991, a team from DuPont, with the goal of improving the company’s maintenance performance, conducted a study of 15 of America’s most prestigious companies and dozens of DuPont’s own plants [Hodkiewicz and others, 2009]. The findings revealed that DuPont was spending 10-30% more on maintenance per dollar of plant value compared to industry leaders, while overall plant uptime was 10-15% lower. Recognizing the need for improvement, the team continued their benchmarking efforts over several years, expanding the study to include 140 plants, including award-winning plants in Europe and Japan.

The extensive data collected during this benchmarking process was difficult to digest until the team, led by Ledet, recognized that the behaviours in the plants could be classified into one of five stable domains. Ledet published a figure that graphically portrayed the behaviours of maintenance groups in the manufacturing industry, known as the “Domains of Operation”. Each domain is distinguished by a distinctive attitude and associated rewards, drivers, and behaviours.

Figure 3: Operating Domains as proposed by Ledet (source: reliabilityweb.com)

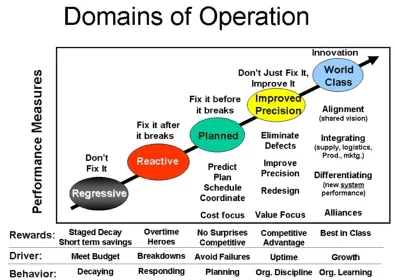

Initially, Ledet proposed three domains: Reactive, Planned, and Improved Precision. However, as the study continued, he added two additional domains, Regression and World-class, to include plants that were being abandoned and those striving to achieve a new level of performance through behaviours associated with organizational learning [Hodkiewicz and others, 2009].

Figure 4: Revised Domains of Operation model as proposed by Ledet (source: reliabilityweb.com)

The Domains of Operation model developed by Ledet and his team continues to be widely cited in a lot of articles and posts. And it’s use of characteristics like rewards, drivers, behaviours aligns quite well with the culture model we discussed earlier.

Personally, what I see as one of the most powerful concepts coming from Ledet’s work around the Domains of Operation is the concept that some domains are stable, and others are not. Although not clearly articulated anywhere, I see this stability – or the lack of it – as a reflection that ways of working, processes, and practices cannot be sustained without a focus on all four elements that make up a reliability culture.

The biggest issue I have with the Domains of Operation is not so much with the model itself, but much more with the many adaptions that have been published. Many of adaptions link specific practices to specific domains, suggesting that these practices are done in one part of the journey. For example, Time Based Maintenance (TBM) is shown as a practice for the planned maintenance domain, and Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM) as something you apply in the precision domain.

Some adaptions I have seen in the pasted even went as far as suggesting that Time Based Maintenance is done in the planned domain, Condition Based Maintenance in the Precision Domain, and Predictive Maintenance (PDM) in the World Class Domain. But all this is just plain wrong! The type of maintenance you (need to) do is a function of the failure modes you’re dealing with and the consequences of those potential failures and that means that even in the World Class Domain you will have a combination of Time-Based Maintenance, Condition Based Maintenance and yes even Run-to-Failure Maintenance.

The journey towards higher reliability is one where you build upon practices, not replace them as you improve and you start with the fundamentals that Ledet shared as part of the Manufacturing Game and in his book Don’t just Fix it, Improve it and I have adapted in my Road to Reliability Framework™.

I think that some of the messaging in Ledet’s Domains of Operation model like “fix it after it breaks” and “fix it before it breaks” have been taken too literally by many people and that has developed this common – but flawed – perspective in industry that you apply different maintenance types at different levels of maturity and performance.

So although Ledet’s model is useful, and his work that led to the model was in many ways ground-breaking, I feel that the model has been abused too much to use as a good reference for describing reliability cultures.

A Reliability Maturity Model by Google

More recently a Reliability Maturity Model has been published by Vartika Agarwal and Tracy Ferrell, both employees at Google [Agarwal and Ferrel, 2022]. Although the Reliability Maturity Model proposed by Agarwal and Ferrell is much closer to what I would consider to be a maturity model for culture, it is in my opinion not really tuned towards industries focussed on physical assets.

So, in the absence of a clear reliability maturity model out there, I turned to a profession where the importance of organisational cultures has long been acknowledged as essential to success: safety.

Learning from the Safety Journey

Over my 25+ years of experience in the industry there has always been one clear constant factor: the importance of safety and the focus on safety within the organisations I worked.

Let’s be honest, the improvement of safety in industry has been a long and difficult journey and many industries had defining events and investigations that led us to where we are today. Some that heavily influenced my career and knowledge were:

- Piper Alpha in 1988 which to date remains the worst offshore disaster in terms of lives lost. Although Piper Alpha occurred well before I started by career in 1997, it influenced the industry deeply with the Cullen inquiry which eventually led to the Offshore Safety Act in 1993 and the Offshore Installations (Safety case) Regulations in 1992

- Texas City Refinery Explosion in 2005 which killed 15 workers. Following the incident the Baker Panel Report was commissioned and published in 2007 and had a strong focus on the importance of safety culture. Many organisations around the globe realised that they exhibited similar issues and weaknesses. In Shell (where I worked at the time) it led to a significant, global effort to improve Asset Integrity through both improved management frameworks as well as physical improvements of many assets around the globe. I was lucky enough to be part of one the global teams developing the initial Asset Integrity framework documentation.

- There have sadly been many more incidents that influenced the discussion around safety culture like Bhopal, Chernobyl, and Deep Water Horizon / Macondo.

There are many parallels between safety and reliability and I will always remember the phrase that Terrence O’Hanlon shared during a CRL workshop in Melbourne: “Just like Safety, Reliability is everybody’s business” – it’s powerful, it’s true and it has always stuck with me.

And given everything that has occurred within the domain of industrial safety, and the many lives lost along the way, I think it’s fair to say that safety is probably decades ahead of reliability in terms of driving culture change in many organisations around the world.

Of course, the level to which this has been achieved varies from organisation to organisation, but in general, some of the bigger improvements referenced in industry literature include:

- Increased focus on hazard identification and risk assessment: Many organizations have implemented processes for identifying and evaluating potential hazards in the workplace, and for implementing controls to mitigate those risks. This includes the use of tools such as hazard analysis techniques as well as risk assessment tools.

- Greater emphasis on employee participation: Many organizations have recognized the importance of involving employees in safety efforts, and have implemented programs and processes to encourage their participation. This includes safety committees, safety suggestion programs, and other mechanisms for soliciting input from employees.

- Improved training and education: Many organizations have invested in training and education programs to help employees understand the importance of safety and how to work safely. This includes both formal training programs and informal awareness-raising efforts.

- Better incident investigation and analysis: Organizations have also made efforts to improve their incident investigation and analysis processes, with the goal of identifying root causes and implementing corrective actions to prevent future incidents. This includes the use of techniques such as root cause analysis and incident review boards.

- Greater use of technology: Many organizations have also made use of technology to improve safety, such as through the use of automation, sensor systems, and other types of monitoring and control systems.

These improvements and many other efforts over the years have helped to create a stronger safety culture in many industries, resulting in reduced injuries and fatalities, and a safer work environment.

I do believe that stronger regulation in many countries around the globe has played a huge role in this improvement in both safety performance and safety culture. We are unlikely to ever see that kind of legislative focus on reliability, which means that organisations will need to be more internally motivated to improve as the external motivators will be significantly less.

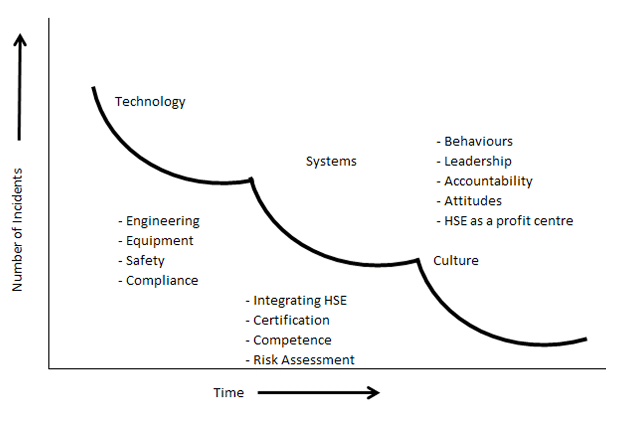

Figure 5: Safety focus areas (Hudson, 2007)

I also firmly believe that the majority of industrial organisations has been approaching reliability improvement very much like how safety used to be approached: technology solutions with insufficient focus on improving systems of work and even less on reliability culture. And unfortunately, all too often those technology solutions are introduced too late in an asset’s life – after start-up when reliability is already an issue. Instead, reliability should be introduced much earlier in the life cycle of an asset during the early stages of design, but that’s something to discuss in another article.

In the meantime, we need to realise that we must learn from the safety journey and ensure we have certain minimum levels of technology in place, effective systems and processes for the key processes that drive reliability, leadership to drive the required changes and an effective reliability culture to sustain the improvements over time.

And over the last few decades a lot of work has been done in the area of safety cultures. James Reason, a psychologist and human error expert, discussed the concept of safety culture in his 1990 book, “Human Error.” He identified five elements that characterize a strong safety culture within an organization. These elements are:

- Informed Culture: Organizations collect data to understand risks and fix potential problems. Open communication and learning from mistakes are essential.

- Reporting Culture: Employees report safety concerns and incidents without fearing punishment. This helps identify and fix weaknesses in the system.

- Just Culture: Organizations focus on finding root causes of incidents rather than blaming people. This encourages reporting and learning from errors.

- Flexible Culture: Companies adapt quickly to changes and respond effectively to safety challenges. Cross-functional collaboration and open communication are key.

- Learning Culture: Companies are committed to continuous improvement in safety. They learn from incidents, invest in training, and encourage feedback.

There have been other models for safety cultures, but most of these, just like Reason’s five elements, are not a reflection of maturity of the safety culture, but more of the elements required to achieve an effective safety culture.

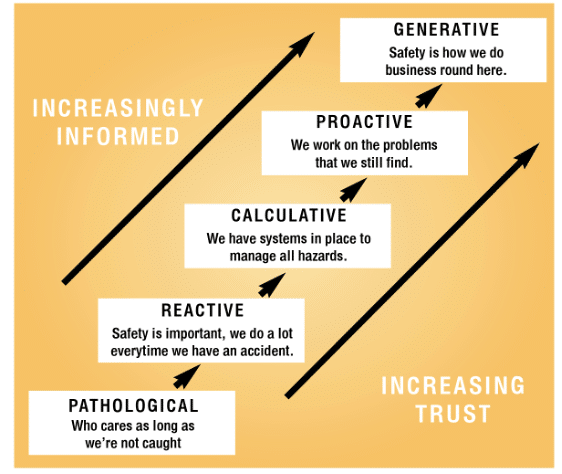

The Safety Culture Ladder by Prof Dr Hudson

However, In the late 1990s to early 2000s, Professor Patrick Hudson developed the Safety Culture Ladder based on his work done in high-risk industries (primarily with Shell in the oil & gas space, and aviation). And since its launch the Safety Culture Ladder model has gained attention and recognition across the world for its practical approach to understanding and improving safety culture within organizations.

Figure 6: Safety Culture Ladder as defined by Professor Hudson

The Safety Culture Ladder, also known as the Safety Maturity Ladder, is a way to understand and improve an organization’s safety culture by looking at attitudes, actions, and values related to safety. It has five levels:

- Pathological (Level 1): At this level, organizations only focus on meeting the bare minimum legal requirements and avoiding penalties. They tend to put the blame on workers when accidents happen and might even ignore or hide safety issues until a crisis occurs. Their focus is on short-term gains, and there is little commitment to developing a strong safety culture.

- Reactive (Level 2): Organizations in this category recognize the significance of safety but mostly act after accidents occur. Reactive cultures often rely on a “trial and error” approach to safety, and learning is mostly driven by accidents and near misses. While some safety processes and systems may be in place, they are not consistently implemented or maintained.

- Calculative (Level 3): At the calculative level, organizations take a more systematic approach to safety management, implementing formal safety policies, procedures, and systems. Metrics and performance indicators are used to measure safety performance, and there is a focus on continuous improvement. However, the safety culture is mainly driven by rules and regulations, and employees may not be fully engaged in safety practices.

- Proactive (Level 4): Proactive organizations actively work to identify and address potential safety risks before they result in accidents. They consider safety an essential part of their daily operations and emphasize employee involvement and ownership of safety initiatives. A proactive safety culture fosters open communication and collaboration between senior management and employees, and safety performance is considered a key indicator of organizational success.

- Generative (Level 5): At the highest level, safety is fully integrated into the organization’s values, beliefs, and everyday activities. A generative safety culture is marked by a deep commitment to safety excellence, with everyone in the organization actively engaged in identifying and managing safety risks. Continuous learning and improvement are emphasized, and safety performance is regarded as a shared responsibility and a source of pride for the organization.

The Safety Culture Ladder model can help organizations assess their current safety culture and identify areas for improvement. By understanding their position on the ladder, organizations can develop targeted strategies and interventions to enhance their safety culture and ultimately reduce the risk of accidents and injuries.

Strengths & Weaknesses of the Safety Culture Ladder

When you read industry sources that reflect on the Safety Culture Ladder a number of important strengths are often highlighted, that make it a useful tool for organizations looking to improve their safety culture:

- Comprehensive framework: The model offers a well-rounded approach to understanding and evaluating safety culture, considering attitudes, behaviors, values, policies, and systems.

- Clear progression: The model outlines different stages of safety culture maturity, helping organizations identify their current position and the steps needed to improve.

- Encourages continuous improvement: The model promotes ongoing improvement by emphasizing proactive measures to address safety risks before incidents occur.

- Engages employees: The model highlights the importance of employee involvement in safety initiatives, emphasizing open communication, collaboration, and shared responsibility.

- Applicable to various industries: The model can be used across different industries and organizations, making it a versatile and adaptable tool for assessing and improving safety culture.

- Focus on values and culture: The model stresses the importance of integrating safety into an organization’s values and daily operations, promoting long-term safety excellence.

As with everything the model also has its share of weaknesses and limitations and some of the most quoted weaknesses and restrictions include:

- Subjectivity: Assessing safety culture can be subjective and the model lacks specific quantitative metrics, which may lead to inconsistencies in evaluations and comparisons. That said I don’t think we’ll ever end up with quantitative metrics that can assess a safety culture consistently across a wide range or organisations and industries, so for me this is not an issue.

- One-size-fits-all approach: The model’s generic framework may overlook unique safety challenges and risks faced by individual organizations due to specific industry or organizational contexts. This weakness is also a strength in my view, in the sense that having a model that can be used across many different industries and organisations creates a common framework that we can use to compare and discuss experiences, practices and outcomes.

- Complexity of cultural change: The model doesn’t provide specific guidance on implementing cultural change or addressing challenges organizations might face during the process, and the fact that it shows culture as 5 ‘steps’ on a ladder may lead to many people oversimplifying the issue. I guess that is something we have to manage as we use the model.

- Overemphasis on linear progression: The model presents safety culture maturity as a linear progression, which may oversimplify the complex development of safety culture. In reality, progress might not always be linear.

- Limited focus on external factors: The model primarily focuses on internal factors, but external factors like regulatory changes, industry trends, or technological advancements can also impact safety culture. The model may not address these factors adequately.

- Risk of complacency: Organizations at a high level of safety culture maturity may become complacent, leading to a loss of focus on continuous improvement and a potential decline in safety performance. Personally, I find this not very applicable as the whole point of higher maturity levels is understanding that it is a journey of continuous improvement and that we can always do better. Organisations that are complacent have simply not reached the higher stages of maturity, or have slipped down the ladder.

In his article, Why Safety Cultures Don’t Work, Professor Andrew Hopkins argues that focusing on changing the way people think and feel about safety (in the oil and gas industry) often yields disappointing results. Instead, companies should concentrate on “the way we do things around here,” which focuses on people’s actions rather than their thoughts. He provides the example of seatbelt legislation, where a change in behaviour eventually led to a change in people’s thinking about safety.

For me this critique really means that our model for what constitutes culture should not just focus on values, behaviours, and role models but also very much on the 4th element of work processes & practices.

Introducing the Reliability Culture Ladder

I’ve found the Safety Culture Ladder very useful, practical, easy to understand and easy to use. And it’s widespread use around the globe suggests that I am not the only one who thinks that. So, it forms a great basis for a reliability maturity model, as long as we ensure that our definition of a reliability culture is sound and addresses the critique from Professor Andrew Hopkins which the reliability culture model, I introduced earlier in this article clearly does.

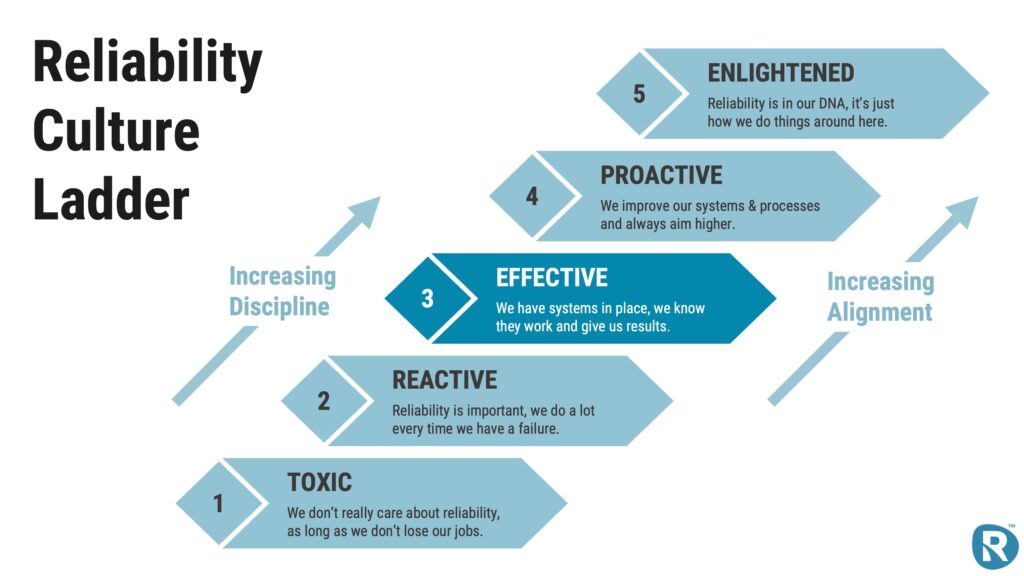

Taking all the above into account, I have developed a Reliability Culture Ladder that distinguishes 5 levels of maturity for a reliability culture:

Figure 7: Reliability Culture Ladder

Importantly this model leverages the strengths of the Safety Culture Ladder, but simplifies some of the language to terminology that we can more easily use and explain within our organisations. It allows us to keep a focus on work processes and practices as long as we stick to our earlier definition of what constitutes a reliability culture. And this model will avoid the risk of pigeon-holing certain practices to specific stages of maturity or vice versa.

The five levels of reliability culture defined in the Reliability Culture Ladder are:

- Toxic

- Reactive

- Effective

- Proactive

- Enlightened

These terms were carefully chosen for the following reasons:

- Toxic was chosen as the lowest level of reliability culture as it is a word that gained widespread use in modern-day language beyond its original meaning of poisonous. Toxic is often used when referring to people, their behaviors, and their attitudes. A toxic reliability culture is a harmful culture, that damages the organisation and the people within the organisation.

- Reactive was chosen as the 2nd lowest level of reliability culture. The term ‘reactive reliability culture’ will be inherently understood across industries given the common understanding of reactive practices, where efforts to fix or improve issues only take place after (major) failure events or incidents.

- Effective was chosen as the mid-level reliability culture to clearly state that for many organisations a mid-tier reliability culture may well be sufficient, and effective enough to achieve the organisations goals. Effective indicates that things work and result are achieved.

- Proactive was chosen as the 2nd highest tier to describe a reliability culture and contrasts the well-known term of ‘reactive’. Proactive is often used, and inherently understood, but probably not well defined.

- Enlightened was chosen as the top tier for a reliability culture as the term will immediately highlight that few organisations will achieve the enlightened stage. The term High Reliability Organisation (HRO) was deliberately not used, as HROs are a complex concept, and remain difficult to define as highlighted by Professor Andrew Hopkins in his paper titled “The Problem of Defining High Reliability Organisations” (2007). Furthermore, HROs typically operate in hazardous industries and represent a model that is not necessarily a good fit for many organisations that struggle with poor reliability culture. And we want level 5 to be a cultural role model that most organisation could relate to, even if they may not decide to aspire to that level of performance.

Let’s have a brief look at each of these levels of reliability culture maturity:

Level 1 – Toxic Reliability Culture

At this level the organisation not only has a reactive approach to reliability, it is simply not interested in reliability. There is no consistent attempt to improve performance or even the realisation of the potential benefits that increased reliability could bring to the organisation in terms of increased uptime, reduced maintenance costs and a better, safer place to work.

With the reactive work environment come the expected high levels of stress and frustration, but this is seen ‘normal’ and ‘just the way it is’.

The organisation celebrates its ‘overtime heroes’ who rapidly, with great skill restore equipment and production after major breakdown events. The focus is on fixing fast, instead of fixing forever. There is no real effort to conduct root cause analysis or defect elimination.

This level of reliability culture can be characterised by people in the organisation reflecting on reliability as follows: “we don’t care about reliability, as long as it doesn’t impact me, or we don’t get caught out.”

The relationship between the Operations and Maintenance departments is often subservient with maintenance deferring to operations and simply working to fix what is broken.

Level 2 – Reactive Reliability Culture

This is the reliability culture maturity that most industrial plants find themselves at. The organisation is always firefighting, chasing today’s emergencies, with high levels of stress and the lack of reliability culture is directly impacting the bottom line with production downtime and high maintenance costs.

However, unlike in the toxic reliability culture, at this level the organisation is often aware that it is reactive and wishes it was different, but the organisation is unable to really drive improvement or sustain any improvements.

There is often a lack of leadership to emphasize the importance of reliability (reliability is not a core value) or if it is spoken about there is strong misalignment between what is said, what is done and what is rewarded. There is still a very clear ‘overtime heroes syndrome’ with staff rewarded for fast responses to breakdowns and production outages.

The organisation lacks effective planning & scheduling leading to poor productivity and high amounts of break-in work. Typically, a Preventive Maintenance (PM) Program is in place, but it is ineffective and inefficient. There are attempts at root cause analysis, but these are not sustained, nor effective and don’t lead to material improvements in performance. The organisation is stuck in “forever fixing, instead of fixing forever”.

The levels of stress and frustration in the workforce remain high, but a key difference is the understanding that things could be better, and part of the frustration is around the lack of improvement.

The relationship between the Operations and Maintenance departments is often adversarial. Maintenance is expected to fix breakdowns fast but is frustrated by being put in this position so frequently. There is no champion for reliability within the organisation.

The reliability culture in the organisation at this level can be characterised by the phrase: “Reliability is important, we do a lot to improve every time we have a failure”

Level 3 – Effective Reliability Culture

At level 3, the organisation has turned a corner, and has much lower levels of reactive maintenance and the culture has become effective.

The core processes of planning & scheduling, preventive maintenance, root cause analysis and defect elimination are defined, documented, and effectively implemented. However, there remains significant room for improvement.

Continuous improvement is in place, but does lack effectiveness and improvements are typically made after incidents or major downtime events, rather than through a conscientious, continuous improvement loop.

Culturally the importance of reliability has been established and is typically documented in a policy to highlight reliability as a value in the organisation. However there remains a discrepancy between reliability being presented as a core value and the behaviours, rewards, and role modelling within the organisation. Not all elements of the overtime heroes syndrome have been eliminated yet.

The stress and frustration levels in the organisation have significantly reduced. Teams understand their role, typically have the time to work to agreed processes and deliver quality work. On occasion when major incidents or breakdowns occur, the organisation might slip back and exhibit reactive behaviours but these are exceptions and typically self-corrected.

The relationship between Operations and Maintenance has become constructive with both departments understanding they work towards shared goals and realise the value both teams bring to the table.

An effective Reliability Culture can be summarised by the phrase: “We have systems in place, we know they work and give us results”.

Level 4 – Proactive Reliability Culture

At level 4 a proactive reliability culture has emerged. The organisation has undergone a significant transformation and is hardly recognisable.

Stress and frustration levels have significantly come down and frustration that might exist in the organisation reflects a deep desire to improve further, faster.

Not only are the core processes of planning & scheduling, preventive maintenance, root cause analysis and defect elimination fully implemented and highly effective, there is a structured, continuous focus on improvement. Improvement takes place through staff-initiated improvements identified as part of the day-to-day execution of work, as well as through structured, formalised reviews of the work processes. All processes have designated Process Owners who conduct these reviews and work with the teams in the business to ensure processes are both effective and efficient. A consistent effort is made to identify practices worth repeating from other peers within their industry.

Highly effective process in place for planning & scheduling with a good understanding of where, why, and how productivity is lost and clear plans to continuously improve. The PM Program is well-established, effective, and efficient, but still continuously reviewed for improvement opportunities. Staff understand the principles that underpin an effective and efficient PM program.

The level of proactiveness can be observed through the fact that Root Cause Analysis following major breakdowns or downtime events has now been largely replaced by proactive review of potential reliability threats and defect elimination to address minor issues through frontline involvement.

The overtime heroes syndrome has been eliminated. Breakdowns do happen, but recognition goes out when the root cause has been clearly established and eliminated.

Maintenance and operations have developed their constructive relationship into an effective partnership. They jointly set goals, develop improvements, use multi-disciplinary teams and routinely second personnel into each other’s teams for both professional development as well as enhancing their teamwork.

A proactive Reliability Culture can be summarised by the phrase: “We improve our systems and processes, and always aim higher”.

Level 5 – Enlightened Reliability Culture

Few organisations achieve a Level 5 reliability culture which could be described as enlightened’ and characterised by the phrase “reliability is in our DNA; it’s just how we do business around here.”

At this point reliability is fully reflected in the organisation’s values, behaviours, rewards, and senior leaders across the organisation consistently act as role models. People across the organisation understand that reliability is everybody’s responsibility just like safety and they know and understand their individual role in achieving and improving reliability.

Not only do enlightened reliability cultures understand the importance of continuous improvement, but they are also actively looking at practices outside their own industries that could be adapted for use in their organisation. A lack of improvement is experienced as going backwards.

What’s Next?

Creating a Reliability Maturity Model is helpful, but only if we can put it to practical use. In the near future, I will aim to make this concept of a Reliability Culture Ladder more practical by publishing the following:

- An initial assessment tool that can be used to assess an organisation’s reliability culture. This will go hand-in-hand with a more expanded description of the 5 maturity stages.

- An in-depth article on how to improve the reliability culture of an organisation, in a practical way that will actually succeed within the typical constraints that most maintenance & reliability managers face in their organisation: a lack of resources and a lack of leadership support.

In the meantime, I would be very interested to hear your thoughts and opinions on the Reliability Culture Ladder model.

References

- Agarwal, Vartika & Ferrell, Tracy, 2022, Reliability Maturity Model, USENIX Association, accessed March 2023, https://www.usenix.org/publications/loginonline/reliability-maturity-model

- Carsten Busch, 2017, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ladder-quick-sand-critical-view-safety-culture-carsten-busch/

- Hodkiewicz, Melinda & Burns, Penny & Wallsgrove, Ruth. (2009). Asset Management – A game of snakes and ladders, accessed January 2023, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235339755_Asset_Management_-_A_game_of_snakes_and_ladders

- Hopkins, Andrew, 2007, The Problem of Defining High Reliability Organisations, National Research Centre for Occupational Health and Safety Regulation, accessed March 2023, https://regnet.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2015-05/WorkingPaper_51_0.pdf

- Hudson, P. (2007), “Implementing a Safety Culture in a Major Multi-National”, Safety Science, Vol. 45, No.6, pp. 697–722.

- Ledet, Winston, published by reliabilityweb.com, accessed March 2023, https://reliabilityweb.com/articles/entry/the_abcs_of_failure_getting_rid_of_the_noise_in_your_system